Stalking: Define the Crime

“Stalking is a repetitive pattern of unwanted, harassing or threatening behavior committed by one person against another”. Stalking includes: telephone harassment, being followed, receiving unwanted gifts, and other similar forms of intrusive behavior. All states and the Federal Government have passed anti-stalking legislation. Definitions of stalking found in state anti-stalking statutes vary in their language, although most define stalking as “the willful, malicious, and repeated following and harassing of another person that threatens his or her safety”.

How common is Stalking?

“The National Violence against Women Survey” (NVAW) is a landmark study that collected information about stalking a nationally representative sample of 8,000 women and 8,000 men across the United States. The survey found that 8% of women and 2% of men have been stalked at some time during their lives. This means that 1 out of every 12 women and 1 out of every 45 men have been stalked during their lives.

Who stalks whom?

Men commit most stalking. Four out of every five stalking victims are women. While, high-profile celebrity stalking cases generate considerable media attention, they are relatively rare. Most stalking occurs between people who know each other. Less than one-fourth of women and about one-third of men are stalked by strangers. Women are most likely to be stalked by a current or former intimate partner during the relationship, after it ends or at both points in time.

How is stalking related to domestic violence?

The majority of women who are stalked by current or former intimate partners also report having been physically assaulted these partners and a sizable percentage (1/3) also report having been sexually assaulted by the same partners who stalked them. These important findings suggest that contrary to popular notions about who gets stalked, currently or formerly battered women have the greatest risk of being stalked.

What kinds of stalking behaviors do victims experience?

Female stalking victims most commonly report being followed, spied on, or watched at home, at work or at places of recreation.

- Many also report receiving unwanted phone calls, letters, or gifts, and having restraining or protective orders violated.

- Battered women stalked by their current/former abusive partners report: being harmed, having mail stolen, being watched, receiving unwanted calls at home, being followed, and receiving unwanted visits from their current or former abusive partners.

- Battered women experience multiple, serial forms of violent and harassing stalking behaviors perpetrated against them, sometimes as often as every day.

Are Stalking Victims Threatened with Serious Harm?

Depending on the sample of women studied, different rates of being threatened with serious harm are reported.

Why do Stalkers engage in this Behavior?

Motivation for stalking is not primarily sexual, but is more likely to include anger and hostility towards the victim, often stemming from actual or perceived rejection of the stalker by the victim Victims perceive control and obsessive behavior as primary motives of the stalker.

Types of Stalkers:

Zona and colleagues (1993) have delineated three types of stalkers which are as follows:

Simple Obsessional

A prior relationship exists between the victim and the stalker which includes the following:

- Acquaintance, neighbor, customer, professional relationship, dating, and lover

- The stalking behavior begins after either:

- The relationship has gone “sour”, or

- The offending individual perceives some mistreatment

- The stalker begins a campaign either to rectify the schism, or to seek some type of retribution

Erotomania

- Based on the Diagnostic Statistical Manual, 4th ed. The central theme of the delusion is that another person is in love with the individual

- The delusion often concerns idealized romantic love and spiritual union rather than sexual attraction — “a perfect match”

- The object of affection is usually of a higher status and can be a complete stranger

- Efforts to contact the victim are common, but the stalker may keep the delusion a secret

- Males, seen most often in forensic samples, come into contact with the law during misguided pursuits to “rescue” the individual from some imagined danger

- Females are seen most often in clinical samples

Love Obsessional: Similar to the erotomanic individuals

- The victim is almost always known through the media

- The delusion that the victim loves them may also be held

- The erotomanic delusion is but one of several delusions and psychiatric symptoms — this individual has a primary psychiatric diagnosis

- These individuals may be obsessed in their love, without having the belief that the target is in love with them

- A campaign is begun to make his/her existence known to the victim

Categories of Stalkers

Current Definitions: Mullen et al. (1999) delineated five categories of stalkers based on motivations and context: rejected, intimacy seekers, incompetent, resentful, and predatory.

The Rejected

As a result of relationship dissolution (i.e. estrangement, disruptions, break-ups) from an ex-partner (but inclusive of a parent, friend, or work associate) this type of stalker can be observed desiring a mixture of reconciliation and revenge.

This individual often experiences feelings of loss, frustration, anger, jealousy, malevolence, and depression.

The Simple Obsessional subtype given above closely approximates this type of stalker.

The Intimacy Seeker

These stalkers pursue an intimate relationship with an individual perceived as their true love, but their attentions are not wanted by the object of their affection. The types of stalkers who fall into this category often have a delusional disorder (i.e. erotomania). Those who represent “intimacy seekers” may suffer from other disorders (i.e. schizophrenia, mania) or hold morbid infatuations.

Erotomania and Love Obsessional best represent this category.

The Incompetent

- These intellectually limited and socially incompetent individuals desire intimacy, but the object of their affection does not reciprocate these feelings.

- They often lack sufficient skills in courting rituals.

- They may also display a sense of entitlement: believing they deserve a partner, but lack the ability or desire to engage in subdued, preliminary interpersonal relations.

- Another aspect of these stalkers is that they may have had previous stalking victims.

- Unlike the intimacy seekers, those in the incompetent category do not view the victim as having unique qualities; they are not infatuated with the victim — only attracted, and do not assert that the affection is mutual.

The Resentful

- The goal of this stalker is to frighten and distress the victim.

- These stalkers may also experience feelings of injustice and desire revenge.

The Predatory

- The power and control that comes from stalking a victim gives these stalkers a great deal of enjoyment.

- The stalker often strives to learn more about the victim.

- The stalker may even mentally rehearse a plan to attack the victim.

- Most of these stalkers are diagnosed paraphilias and, compared to the previous four categories, they were more likely to have histories of sexual offense convictions.

Less than half of female stalking victims in the NVAW study reported being directly threatened by their stalkers. In contrast, 94% of battered women in another study reported being threatened with serious harm by their batterer-stalkers.

Are Stalkers Mentally Ill?

Most stalkers are not psychotic, (i.e., have hallucinations/delusions) although many do suffer from other mental problems including depression, substance abuse, and personality disorders.

According to the NVAW survey, slightly more than half of female stalking victims reported their stalking to the police.

Overall, only 13% of female stalking victims reported that their cases were criminally prosecuted. Police were more likely to arrest a stalker when the victim was a woman.

Police were also more likely to refer female than male victims to victim service agencies for support and counseling.

What are the Costs and Consequences of Stalking?

- Victims of stalking experience a number of disruptive psychological consequences of stalking, including significant fear and safety concerns, as well as symptoms of depression, anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder.

- Most stalking victims do not seek mental health services.

- Approximately one-third of female and one-fifth of male stalking victims sought professional counseling.

- Stalking victims reported missing an average of 11 days from work, and 7% indicated that they never did return to their jobs.

- While homicide occurs in only 2% of stalking cases, when it does occur, the victim is most likely to be a former intimate partner

How Can You Help a Victim or Yourself if you are a Victim?

- Provide support and validation because threatening and harassing behavior alone, without accompanying violence are often minimized or discounted.

- Remind the victim to check out the applicable state anti-stalking statutes. Help the victim to develop a paper trail documenting evidence of stalking. Caller ID records, logs of phone calls, copies of threatening letters, pictures of injuries, or of the stalker sitting outside the home, are examples of evidence that may help build a case.

- Inform law enforcement officials about the stalking and provide them with this evidence to support a case. If law enforcement officials refuse to conduct an investigation, consider contacting the prosecuting attorney’s office, or a local victim assistance agency.

- A victim may be eligible to obtain a restraining or protective order. Remember, even restraining orders do not always prevent stalking from escalating into violence.

- Develop a safety plan. Inform friends, neighbors, and co-workers about the situation. Show them a photo of the stalker.

- Consider, obtaining an unlisted phone number for private use, and set up an answering machine to receive calls to the published number.

- Have easy access to a reserve set of: money, credit cards, medication, important papers, keys, and other valuables in case you need to leave quickly.

- Have a safe place in mind that you can go in an emergency.

- Keep the phone numbers of assistance agencies easily accessible.

- Try not to travel alone and always vary your routes.

- Consider carrying a cellular phone with you.

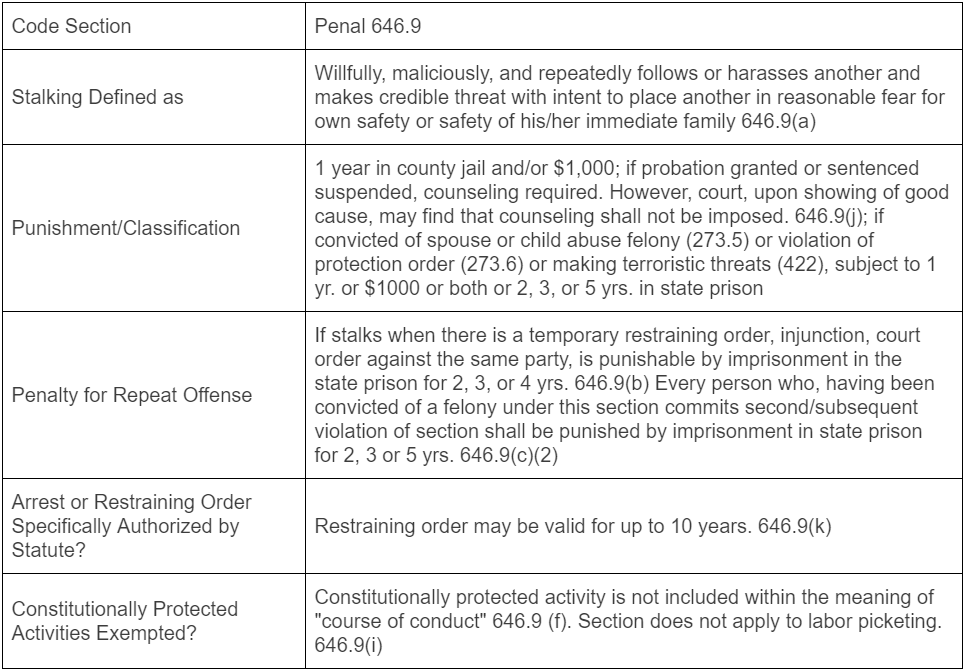

Stalking laws in California:

Bibliography

Diagnostic Statistical Manual, 4th ed. APA

Mechanic, M.B., Weaver, T. L., & Resick, P.A. (1999). Intimate partner violence and stalking behavior: Exploration of patterns and correlates in a sample of acutely battered women, under review.

Meloy, J.R., & Gothard, S. (1995). A demographic and clinical comparison of obsessional followers and offenders with mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 258-263.

Meloy, J.R. (1998). The psychology of stalking. In J.R. Meloy (Ed.) The psychology of stalking: Clinical and forensic perspectives. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Mullen, P. E. (2003). Multiple classification of stalkers and stalking behavior available to clinicians. Psychiatric Annals, 33 (10), 650-656.

Mullen, P. E., & Pathe, M. (1994). The pathological extensions of love. British Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 614-623.

Mullen, P.; & Pathe, M. (1994). Stalking and the pathologies of love. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 28, 469-477.

Mullen, P, E, & Pathe, M. (2002). Stalking. Crime Justice, 29, 273-318.

Mullen, P. E., Pathe, M., & Purcell, R. (2000). Stalking. Psychologist, 13(9), 454-459.

Mullen, P. E., Pathé, M., & Purcell, R. (2001). Stalking: new constructions of human behavior. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 35, (1), 9-16.

Mullen, P.E., Pathe’, M., & Purcell, R. (2001) the Management of Stalkershttp://www.psychinaction.com/uimages//330.pdf

Mullen, P. E., Pathe, M., Purcell, R., & Stuart, G. W. (1999). A study of stalkers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 1244-1249.

Tjaden, P., & Theonnes, N. (1998). Stalking in American: Findings from the national violence against women survey. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice. NCJ Report No. NCJ 169592.

Zona, M. A., Palarea, R. E., & Lane, J. C. (1998). In J. R. Meloy (Ed.), The psychology of stalking: Clinical and Forensic Perspectives (pp. 85-112). New York: Academic Press.

Zona, M. A., Sharma, K. K., & Lane, J. C. (1993). A comparative study of erotomanic and obsessional subjects in a forensic sample. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 38 (4), 894-903.